Obake

Obake (お化け) and bakemono (化け物) (sometimes obakemono) are a class of yokai in Japanese folklore. Literally, the terms mean a thing that changes, referring to a state of transformation or shapeshifting.These words are often translated as ghost, but primarily they refer to living things or supernatural beings who have taken on a temporary transformation, and these bakemono are distinct from the spirits of the dead. However, as a secondary usage, the term obake can be a synonym for yūrei, the ghost of a deceased human being.

A bakemono's true form may be an animal such as a fox (kitsune), a raccoon dog (tanuki), a badger (mujina), a transforming cat (bakeneko), the spirit of a plant — such as a kodama, or an inanimate object which may possess a soul in Shinto and other animistic traditions. Obake derived from household objects are often called tsukumogami.

A bakemono usually either disguises itself as a human or appears in a strange or terrifying form such as a hitotsume-kozō, an ōnyūdō, or a noppera-bō. In common usage, any bizarre apparition can be referred to as a bakemono or an obake whether or not it is believed to have some other form, making the terms roughly synonymous with yōkai.

Yurei

Yūrei (幽霊) are figures in Japanese folklore, analogous to Western legends of ghosts. The name consists of two kanji, 幽 (yū), meaning "faint" or "dim" and 霊 (rei), meaning "soul" or "spirit." Alternative names include 亡霊 (Bōrei) meaning ruined or departed spirit, 死霊 (Shiryō) meaning dead spirit, or the more encompassing 妖怪 (Yōkai) or お化け (Obake).

Like their Chinese and Western counterparts, they are thought to be spirits kept from a peaceful afterlife.

Japanese afterlife

According to traditional Japanese beliefs, all humans have a spirit or soul called a 霊魂 (reikon). When a person dies, the reikon leaves the body and enters a form of purgatory, where it waits for the proper funeral and post-funeral rites to be performed, so that it may join its ancestors. If this is done correctly, the reikon is believed to be a protector of the living family and to return yearly in August during the Obon Festival to receive thanks.

However, if the person dies in a sudden or violent manner such as murder or suicide, if the proper rites have not been performed, or if they are influenced by powerful emotions such as a desire for revenge, love, jealousy, hatred or sorrow, the reikon is thought to transform into a yūrei, which can then bridge the gap back to the physical world.

The yūrei then exists on Earth until it can be laid to rest, either by performing the missing rituals, or resolving the emotional conflict that still ties it to the physical plane. If the rituals are not completed or the conflict left unresolved, the yūrei will persist in its haunting.

Appearance

In the late 17th century, a game called Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai became popular, and kaidan increasingly became a subject for theater, literature and other arts. At this time, they began to gain certain attributes to distinguish themselves from living humans, making it easier to spot yūrei characters.

Ukiyo-e artist Maruyama Ōkyo created the first known example of the now-traditional yūrei, in his painting The Ghost of Oyuki.

Today, the appearance of yūrei is somewhat uniform, instantly signalling the ghostly nature of the figure, and assuring that it is culturally authentic.

White clothing - Yūrei are usually dressed in white, signifying the white burial kimono used in Edo period funeral rituals. In Shinto, white is a color of ritual purity, traditionally reserved for priests and the dead. This kimono can either be a katabira (a plain, white, unlined kimono) or a kyokatabira (a white katabira inscribed with Buddhist sutras). They sometimes have a hitaikakushi (lit., "forehead cover"),[dubious – discuss] which is a small white triangular piece of cloth tied around the head.

Black hair - Hair of a yūrei is often long, black and disheveled, which some believe to be a trademark carried over from Kabuki Theater, where wigs are used for all actors. However, this is a misconception. Japanese women traditionally grew their hair long and wore it pinned up, and it was let down for the funeral and burial.

Hands and feet - A yūrei's hands dangle lifelessly from the wrists, which are held outstretched with the elbows near the body. They typically lack legs and feet, floating in the air. These features originated in Edo period ukiyo-e prints, but were quickly copied over to kabuki. In kabuki, this lack of legs and feet is often represented by the use of a very long kimono, or even hoisting the actor into the air by a series of ropes and pulleys.

Hitodama - Yūrei are frequently depicted as being accompanied by a pair of floating flames or will o' the wisps (Hitodama in Japanese) in eerie colors such as blue, green, or purple. These ghostly flames are separate parts of the ghost rather than independent spirits.

Classifications

Yurei

While all Japanese ghosts are called yūrei, within that category there are several specific types of phantom, classified mainly by the manner they died or their reason for returning to Earth.

- Onryō - Vengeful ghosts who come back from purgatory for a wrong done to them during their lifetime.

- Ubume - A mother ghost who died in childbirth, or died leaving young children behind. This yūrei returns to care for her children, often bringing them sweets.

- Goryō - Vengeful ghosts of the aristocratic class, especially those who were martyred.

- Funayūrei - The ghosts of those who died at sea. These ghosts are sometimes depicted as scaly fish-like humanoids and some may even have a form similar to that of a mermaid or merman.

- Zashiki-warashi - The ghosts of children, often mischievous rather than dangerous.

- Samurai Ghosts - Veterans of the Genpei War who fell in battle. Warrior Ghosts almost exclusively appear in Noh Theater. Unlike most other yūrei, these ghosts are usually shown with legs.

- Seductress Ghosts - The ghost of a woman or man who initiates a post-death love affair with a living human.

Buddhist Ghosts

There are two types of ghosts specific to Buddhism, both being examples of unfullfilled earthly hungers being carried on after death. They are different from other classifications of yūrei due to their wholly religious nature.

- Gaki

- Jikininki

Ikiryo

In Japanese folklore, not only the dead are able to manifest their reikon for a haunting. Living creatures possessed by extraordinary jealousy or rage can release their spirit as an ikiryō 生き霊, a living ghost that can enact its will while still alive.

The most famous example of an ikiryo is Rokujo no Miyasundokoro, from the novel The Tale of Genji.

Obake

Yūrei often fall under the general umbrella term of obake, derived from the verb bakeru, meaning "to change"; thus obake are preternatural beings who have undergone some sort of change, from the natural realm to the supernatural.

However, Kunio Yanagita, one of Japan's earliest and foremost folklorists, made a clear distinction between yūrei and obake in his seminal "Yokaidangi (Lectures on Monsters)." He claimed that yūrei haunt a particular person, while obake haunt a particular place.

When looking at typical kaidan, this does not appear to be true. Yūrei such as Okiku haunt a particular place -in Okiku's case, the well where she died-, and continue to do so long after the person who killed them has died.

Hauntings

Yūrei do not wander at random, but generally stay near a specific location, such as where they were killed or where their body lies, or follow a specific person, such as their murderer, or a beloved. They usually appear between 2 and 3 a.m, the witching hour for Japan, when the veils between the world of the dead and the world of the living are at their thinnest.

Yūrei will continue to haunt that particular person or place until their purpose is fulfilled, and they can move on to the afterlife. However, some particularly strong yūrei, specifically onryō who are consumed by vengeance, continue to haunt long after their killers have been brought to justice.

Famous hauntings

Some famous locations that are said to be haunted by yūrei are the well of Himeji Castle, haunted by the ghost of Okiku, and Aokigahara, the forest at the bottom of Mt. Fuji, which is a popular location for suicide. A particularly powerful onryō, Oiwa, is said to be able to bring vengeance on any actress portraying her part in a theater or film adaptation.

Exorcism

The easiest way to exorcise a yūrei is to help it fulfill its purpose. When the reason for the strong emotion binding the spirit to Earth is gone, the yūrei is satisfied and can move on. Traditionally, this is accomplished by family members enacting revenge upon the yūrei's slayer, or when the ghost consummates its passion/love with its intended lover, or when its remains are discovered and given a proper burial with all rites performed.

The emotions of the onryō are particularly strong, and they are the least likely to be pacified by these methods.

On occasion, Buddhist priests and mountain ascetics were hired to perform services on those whose unusual or unfortunate deaths could result in their transition into a vengeful ghost, a practice similar to exorcism. Sometimes these ghosts would be deified in order to placate their spirits.

Like many monsters of Japanese folklore, malicious yūrei are repelled by ofuda (御札), holy Shinto writings containing the name of a kami. The ofuda must generally be placed on the yūrei's forehead to banish the spirit, although they can be attached to a house's entry ways to prevent the yūrei from entering.

In popular culture

In ukiyo-e

Yūrei were a popular subject matter for ukiyo-e artists. Many artists created scenes from ghostly Kabuki plays, or attempted to capture the images of real yūrei in ghost portraits.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi's series New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts is typical of Edo period yūrei prints, recreating some of Japan's most famous ghosts.

In 1830, Katsushika Hokusai included yūrei in his One Hundred Tales (Hyaku monogatari) series.

Yurei-ga gallery at Zenshoan Temple

Zenshoan(全生庵) Temple in Tokyo, Japan is known for its collection of yūrei paintings, known as the Yūrei-ga gallery. The 50 silk paintings, most of which date back 150 to 200 years, depict a variety of apparitions from the forlorn to the ghastly.

The scrolls were collected by Sanyu-tei Encho(三遊亭円朝), a famous storyteller (rakugo artist) during the Edo era who studied at Zenshoan. Encho is said to have collected the scrolls as a source of inspiration for the ghostly tales he loved to tell in summer.

They are open for viewing only in August, the traditional time in Japan for ghost stories.

In fiction

Yūrei have always been a major part of Japanese fiction, with almost every writer of note[according to whom] turning his hand to kaidan at one time or another. During the Edo period in particular, a game called Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai became popular. This game lead to a demand for ghost stories and folktales to be gathered from all parts of Japan and China.

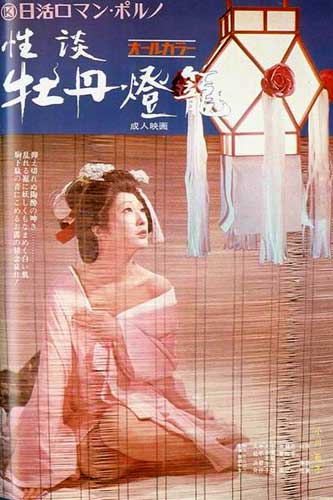

Early popular kaidan, such as Botan Doro, were translated from Chinese folktales and given a Japanese setting. Other yūrei originate in Japan, either as local legends or original stories.

- Otogi Boko (1666) - Asai Ryoi

- Ugetsu Monogatari (1776) - Ueda Akinari

- Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1904) - Lafcadio Hearn

- Maya Kakushi no Rei - Kyōka Izumi

- Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro - Shigeru Mizuki

- Ring (1991) - Koji Suzuki

In film

The first yūrei movies were adaptations of existing kaidan Kabuki plays, such as Botan Doro in 1910, and Yotsuya Kaidan in 1912. New versions of these popular kaidan have been filmed once a decade ever since.

Yūrei films have changed with the various trends in Japanese cinema over the years, never completely leaving the screens. In recent times of the 1990s and beyond, the J-Horror boom has spread the image of the yūrei beyond Japan and into the popular culture of Western countries.

- Ring

- Ju-on

- Kairo

- Dark Water

- Kwaidan

- One Missed Call

- Shikoku

- Ugetsu Monogatari

- After Life

- Dreams

- Rasen

- Throne of Blood

- The Grudge

- Masters of Horror-Dream Cruise

- Shutter

*Marked in bold are those film that are really popular among all the peoples and country.

![[J-BLOG] Map, Culture & Traditional, Etc.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhvmfEXojE4IaQHEj7WJFFqXpc3QG9Ha9bRblYtkTG45gtZEvAQVzCYNBMEk9AZt7shLWsSI-b7qM1JKgtTeaxkQC4cI557LmRMY40UOkXKjybg3WIIVXCrwdfnFlpWjha0CFeeTp9DPSk/s1600-r/j-blog_banner.png)